Louisiana Medicine - Ancient & Modern

Acadians, Creoles & Cajun settlers

Introduction

Before 1713, Acadia was a French colony predominantly developed by colonists from the Mediterranean regions of Brittany, Normandy, Picardy, and Poitou — an area that endured exceptional hardships in the late 16th and early 17th decades.

In 1628, a series of religious wars between Catholics and Protestants ended with famine and disease. More than 10,000 individuals left for the colony established by Samuel Champlain in 1604 known as "La Cadie" or Acadia when economic conflicts ripened in southern France.

One of the first European colonies in North America was the region, which included what is now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and a portion of Maine.

The New France Company hired as indentured servants settlers from coastal France.

For five years, fishers, peasants, and trappers helped to compensate the business for the travel and equipment it had supplied with their labor.

Colonists formed partnerships with local Indians in the New World, who usually favored French settlers over British settlers because, unlike the British who took all the territory they could, Acadia's mainland French did not enter Indian hunting grounds inside.

History

Oral tradition and folklore have long framed the more significant part of the Acadian cultural heritage.

Louisiana's Acadian folklore expresses a culture traditionally centered on family life and child-rearing, Catholicism's rituals and sacraments, and beliefs that diseases and other issues have spiritual rather than biological causes.

One of the profound wisdom of these people is to recover from an illness with the assistance of different herbs that have sprouted throughout their inhabitant lands. Moreover, this knowledge is brought by them transmitted through their European ancestry but also inherited from different cultures.

Louisiana herbs, and plants, in particular, have long been used as essential medical treatments. Historically, the vast majority of pharmacopeias of doctors were packed with plants.

These healing plants have traditionally been combined with prayer and rituals to treat diseases; however, little information is available on the actual effectiveness of most of the treatments, as the Acadians preserved their traditions orally and not in writing.

Each plant can be a living embodiment of a pattern, of vitality combined in a scheme.

As such, there are specific characteristics in the plant that show its medicinal characteristics from the way it develops, where it grows, and what it represents for our perceptions.

Each is a symbol/signature that demonstrates the intention of the remedy and how it should be used.

Signatures operate under the resemblance between a pathology, organ, individuals, and a plant.

By the universal law of correspondence between macrocosm and microcosm, this can be a general foundation for healing for all peoples, operating at all levels, be it spiritual, psychological, or physical.

Acadians lived in isolated communities until the end of the 19th century, with minimal contact with anyone outside their lands. This enabled them to maintain the practices of

their ancestors, their language (derived primarily from France's Poitou region), their cuisine, festivities, and oral traditions: songs, tales, and legends that have gone from

down the generations since their arrival in the 17th century.

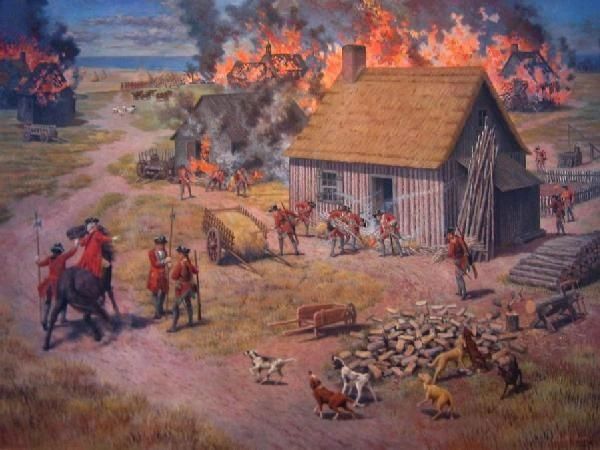

In 1954 France walked over productive fishing, and fur trapping attempts to the "Seven Years ' War" with Great Britain. In this way, France was beaten providing its colonies. The Great Disturbance expatriated the Acadians during the same era. In other regions, including France and Louisiana, the expatriated Acadians moved. In Louisiana, residents of different cultures, including French Creole and Cajun, began to settle.

Thus, although from different backgrounds, the Acadians, French, Cajuns, and Creoles shared prevalent cultures mainly in Agriculture and held shrewd information crops as well as flowers comprising essential oils with various uses i.e., medical and aromatic culinary.

In the development of aromatherapy, herbal medicine from crops and essential oils play a significant part. Herbs used for meat and medical reasons were crucial for life-enhancing benefits. Incense and oil aromatic plants were active in both medicinal and religious activities as well as in oils and perfumes of fragrance.

Aromatherapy was a term Rene-Marice Gattefosse created in 1937. A French chemist, after he endured skin burn in 1910, he found Lavender oil to be an efficient cure.

Herbal Medicine

We present some of the important plants used by these cultures in foods and medicines.

- Elderberry - Known in French Acadian as "Sureau", the elderberry plant was pretty useful with almost every part being used curatively that is from the flower down to the roots through the leaves and stem. For instance, all parts were used for their anti-inflammatory and calming attributes.The flowers were used for measles the stem pith to cleanse eye infections and buds for chills, fever, or headache.

Teething babies would be offered herbal tea from the elderberry as well as dressing the skin in case of wounds or swellings."“Boil the pith of elderberry and wash your eyes with that.”

- Sassafras - All parts of this plant, including the twig leaves, stems, roots flowers, and fruits were used in culinary, medicinal an aromatic purpose. For culinary purposes, Sassafras albidum is a vital ingredient in ancient root beer, making root tea that is deemed to “warm the blood.” It’s also suitable for Gumbo file, an essential component in Creole cuisine. Medically it is used to extract Poison from insect bites, treating acne, urinary disorders, and fevers and also in treating wounds by directly rubbing the leaves to it.

Essential oil with a high safrole content was obtained from its dried root bark by steam distillation. The essential oil also contains other chemicals i.e., camphor, eugenol, asarone, and various sesquiterpenes hence Sassafras oil, that was once used as a fragrance in soaps and perfumes, food and for aromatherapy.

Sassafras twigs were also anciently used for fire starters and as toothbrushes.

“Give them tea made with sassafras root. Put a bit of whiskey in the tea, and drink that two or three times a day.”

- Goat Weed - Also known as thé cabri ( herbe cabri ), or goat tea, this subtly beautiful and aromatic herb is a local favorite for making a therapeutic beverage for fever, chills, and other influenza type ailments. Some report using it to relieve stomachache, and as a general tonic. Though it is usually served as a hot tea, some use it as a cold drink for its relaxing effects.“For chills, you boil some goat weed to drink.”

- Lizard’s Tail - Herbe à Malo - This plant’s common English name derives from its arching stalk of flowers that mature into a cluster of brown seedpods that resemble a lizard’s tail. It can be found along the waters edge and in swamps. All parts of the plant are used for its antiinflammatory and sedative properties. In Cajun and Creole folk medicine, a tea made from the plant is given to teething babies. The root can be administered externally for wounds and inflammations of the skin. Tea made from the stems, roots, and leaves can be used to treat rheumatism stomach ailments and can also be used for general illness. Some use the mashed plant to make a poultice to apply to wounds.

- Coral Bean, Mamou - With its three parted leaves, the showy stalks of scarlet flowers, and the glossy red beans peeking out of the cracking black pods, the mamou is both a beautiful plant and a powerful medicine. The seeds and root of this plant are used to make a tea or syrup to treat symptoms of the flu, pneumonia, bronchitis, tuberculosis, colds, pleurisy, and whooping cough.A tea made from the leaves is also useful in treating most respiratory problems as well as fever and stomach cramps. In Acadiana, the mamou is a staple plant that has a permanent home in the yards of those who know of its medicinal qualities.“Boil mamou seeds in some water. Drink a small cup every three hours.”

- Lavender - A flower used in the ancient times in bath for its therapeutic purposes and as a perfume as well as for its antiseptic and healing qualities i.e. used to fight insomnia and backaches. It was also used asana essential oil hence aromatherapy thus a high line of culinary products.

- Groundsel Bush - Manglier - Manglier is the hidden jewel of the medicinal plant collection. Little seems to be known about it outside of Louisiana, but it is well known by the Native American, Cajun and Creole communities as an excellent remedy for fevers, chills, congestion, and other cold or pneumonia type symptoms. The leaves of the plant are boiled to make an aromatic yellow/green brew. Because of its strong, bitter taste, it is usually served with honey and lemon, a cough drop, or some whiskey to cut the flavor.“When someone gets a fever, give him some tea made with manglier. Serve it in a coffee cup three time per day.”

- Wormseed - The name of this plant explicitly implies its use. Wormseed is a popular vermifuge in many parts of the world. Locally, it is taken with milk or with food to expel worms from the digestive system. Among the Houma, the leaves are made into a poultice and pressed against the forehead to treat headaches. Since the leaves have a very pungent, herby flavor, it is often used as a food additive, especially as a seasoning for beans to prevent flatulence.“Make a praline with the seeds. Give them that to eat.”

- Bitter Melon - This exotic-looking plant is widely considered to have many health benefits. Its spiky fruit progresses from a pale green color into a vibrant orange and the bottom opens up to reveal bright red seed pouches. The exterior is extremely bitter while the pulp surrounding the seeds is pleasantly sweet. The origins of this plant are disputed. It is a well-known native of Southeast Asia, but it is used by indigenous populations in the Caribbean and Mexico too. In local folk medicine, the fruit is soaked in whiskey and taken for cramps or is applied externally for cuts and burns.“I soak some Bitter Melon in whiskey. I drink a little until the stomachache passes.”

Culinary Heritage

Flavors and herbs dominate the cuisines of Cajun and Creole. It's a Southern U.S. dramatic culinary type that relies heavily on new and dried herbs.

The differences in Creole and Cajun cuisine is attributed to both cultures ' French origins, along with the new ingredients added by the Creoles and Cajuns to French cooking techniques.All cooking styles have culinary origins in Europe, pointing to Spain, Asia, and North America, and to a lesser extent to West Indies, England, Ireland, and Italy.

All cultures take their food very seriously and love baking, dining, and having fun.

The cultural difference between the two cooking methods is that Creoles had access to local markets, and servants cooked their food while Cajuns lived mostly off the ground, were subject to seasonal elements, and generally cooked meals in a large pot.

Cajun and Creole foods are all about the flavor, which is why it relies so much on a variety of herbs and spices.

Culinary spices

- Garlic - A delicious and well-known flavor, garlic is at the top of the must-have list for your Cajun cooking. It ties characters together and creates a rich, satisfying base.

- Parsley - Parsley is both cooling and refreshing. It's overall green taste complements the complex flavors of Cajun dishes. While a sprig of parsley is typically served alongside restaurant dishes, it's culinary uses go far beyond decoration.

- Bay leaves - Bay leaves are perhaps the most undervalued herb in many cooking dishes.

- Cayenne pepper - Although notoriously hot, adding the cayenne pepper is not simply for the heat factor. Any good Cajun cook will tell you that it is about the flavor.

- File - Pronounced FEE-lay, file powder is, quite simply, leaves from the sassafrass tree that are dried and powdered.It is the most important herb to add to your authentic gumbo because it is used to thicken and flavor this traditional dish.Many families pass the shaker of file at the table.

- Summer savory (“sarriette” in French) plays a unique role in Acadian food culture. The herb is the primary seasoning in fricot (rabbit or chicken stew) In the Acadian communities in New Brunswick. It is also a component of the Herbes de Provence mix.

- Gumbo, a popular Cajun sauce, is a perfect creolization example because it comes from multiple cultures.The main ingredient, okra, also gave the name to the dish; first introduced from western Africa was the vegetable, called "guingombo."Spanish and Afro-Caribbean influences are represented by Cayenne, a spicy seasoning used in subtropical cuisines. Today Louisiana inhabitans who eat rice gumbo, usually called gumbo made with okra gumbo fèvi, to distinguish it from gumbo filè, a roux based on French culinary tradition.Just before serving, gumbo filè (also known as filè gumbo) is curdled by adding powdered sassafras leaves, one of Louisiana's Native American cooking contributions.

Some traditional cures and plants

Many Cajun remedies have been acquired from Africans, such as adding bee stings, snakebites, burns, and pains to a poultice of chewing tobacco. Other remedies came from French doctors or folk cures, such as treating stomach pains by putting a warm plate on the stomach, administering ring-worm with vinegar, and treating headaches with a treater's prayers.

Many Cajun remedies are unique to Louisiana: for example, keeping a burning cane reed over an infection, or placing a garlic bracelet over a baby with worms.

Some plants that grow in prairie gardens are preserved by naturalists:

- Liatris spicata (Dense blazingstar), Arnoglossum ovatum (Indian plantain), and Silphium laciniatum (Compass plant).

- Eryngium yuccifolium (Rattlesnake master) and Helianthus mollis (Ashy sunflower)

- Rhexia mariana (Maryland meadow beauty)

- Hydrolea ovata (Blue waterleaf), Vernonia gigantea (Giant ironweed) and Ipomoea sagittata (Salt-marsh morning-glory)

- Big bluestem, Little bluestem, Yellow Indian grass, Switchgrass, Eastern gamagrass, Florida paspalum, and many others.

- Corepsis tripteris (Tall tickseed), Rudbeckia subtomentosa (Sweet black-eyed susans), Monarda punctata (Spotted beebalm),

- Salvia azurea (Blue sage), Physostegia praemorsa (Obedient plant), and Pycnanthemum albescens (White-leaf mountain mint)

- Gaura parviflora (Long-flowered beeblossum) is 7-8 feet tall with tiny beeblossum blooms. Manfreda virginica (American aloe agave)

Many more things are to be said when dealing with Acadian inhabitants. Perhaps one of the most significant part in their history is represented by the Acadian Traiteurs

Healing tradition in Acadia

Folklore can often be mystical, and Acadian folklore regarding Natives depicts a people with supernatural endowments.

They were called "les sauvages" mostly regarded as effective healers.

Among the Acadians, traditional medicine was a much used and

valued resource in a period when skilled medical practicians were scarce.

In rare cases, Acadians went to Mi'kmaw camps in search of remedies.

The Mi'kmaq had a repertoire of incantations and knowledge of medicine that they could exchange for supplies.

Their knowledge of herbal remedies was substantial, and evidence of their transfer to the Acadians who adopted native plant use suggests that the Mi'kmaq taught the Acadians a lot during the establishment period.

The question is, had this always been the prevailing view since the Acadian settlement of the Maritimes, or is it an indicator of a distancing between the two communities after the Acadians were allowed to return?

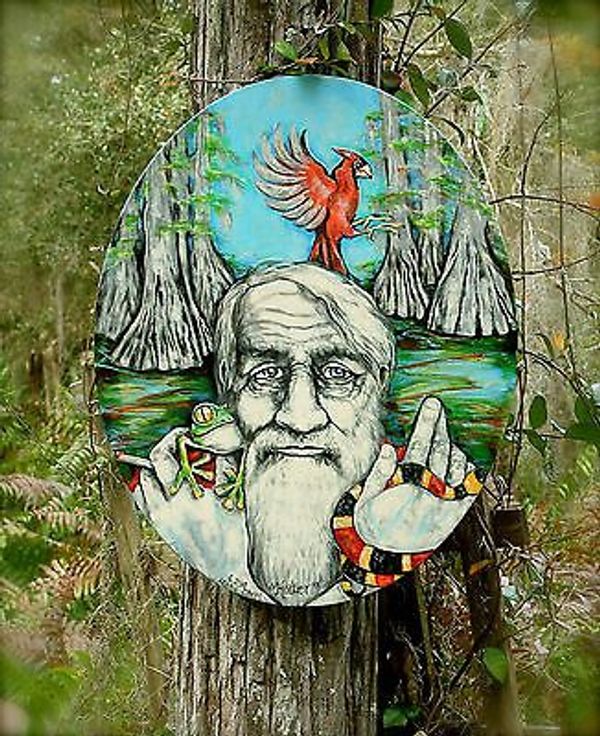

Photo Gallery

While Acadian folklore suggests a deep-rooted fear that natives harbored ill will towards them, the exchange of traditional medicinal remedies during an earlier epoch offers proof of more beneficial encounters.

As this medicinal knowledge exchange took place, the assumption could be created that both communities also had the transfer of folk beliefs and legends.

Europe witnessed a witch-craze spanning the Early Modern Period, and the Acadians were witnesses of trials up to the emigration era. The Acadian psyche was, therefore, receptive to the belief in magic.

Alternatively, in their shamanic traditions, the Mi'kmaq adopted European witchcraft beliefs.

It can also be asserted that the legend and its exchange functioned in both communities to strengthen traditional concepts of hospitality or a good economy.

The Mi'kmaq had their shamans respected for their ability to heal, kill, and prophesy, who were males and females.

Missionary contact restricted the shamans ' influence, who inside their society became almost entirely feared as malicious individuals.

In post-conquest Maritime Canada, the Acadians ' lives centered around the sea and farming, as did their ancestors.

In a pre-electronic age, stories transmitted from generations of legendary people and sagas imported from Renaissance France were recited as a form of entertainment.

There were also the legends of phantom ships, ghosts, and sorcerers of more recent origin.

This overview provides proof of an oral Acadian tradition that originated in the Maritimes, associating their Mi'kmaq neighbors with casting evil spells.

There are legends of Acadian sorcerers, and tied to these legends are those of the Mi'kmaw sorcerer. Marie Comeau, the Acadian sorceress, who married a Mi'kmaw, bridges the image of the Acadian sorcerer and the Mi'kmaw sorcerer. When she married into the Mi'kmaw world, she became a taoueille sorcerer.

- There are other variations in the spelling of this term, with the most common being that of the above: taweille, taweye, and tawoueille. See Yves Cormier Dictionnaire du Francais acadien (Quebec: Fides, 2009), p. 359. -

The geographical usage of taoueille spans from the northeast and southeast New Brunswick; Prince Edward Island, the Ties de la Madeleine, and southern Gaspesie.

According to Pascal Poirier, taoueille is a Mi'kmaq word that entered into the Acadian language.

In more recent times, Yves Cormier reiterates the Native origins of this term by tying it to the Mi'kmaq word Epitewit; the two words are related, but Cormier presents an interesting theory.

Acadian scholars are currently exploring instances of cultural transference between the Acadians and the Mi'kmaq. Ronald Labelle has researched instances of transference in traditional medicine, and there is substantial evidence of both communities adopting remedies from one another.

The Mi'kmaq adopted the use of tansy, while the indigenous adopted the use of labrador tea; but was, in turn, taken from the Mi'kmaq by the Acadians as a preventative of illnesses, such as colds and the flu. Certain informers cite the Mi'kmaq origins of herbal remedies that were recommended as the Mi'kmaq passed by their homes.

For example, tansy was imported by the Acadians and has had multiple uses as poultices and infusions for a variety of ailments, such as bee stings, the flu, and intestinal problems.

Many Acadian cures also have a magic-religious aspect, and there is proof of cultural transference among specific remedies of this nature.

.

The number seven is significant in Acadian and Mi'kmaq cures. For example, the remedy "sept facons de bois," which involves the gathering of seven species of plants, utilizes Mi'kmaq ingredients. Still, it is not sure whether the number seven is of European or Native origin.

Thus, here, the point of view chosen is that of cultural transference as it relates to Acadian legends of Mi'kmaq sorcery and how these legends can provide useful information concerning Acadian-Mi'kmaq relations.

Who was the French sorcerer in Early Modern France, and how can such a definition apply to sorcery in Acadia? According to Jean-Michel Sallmann, in France, the sorcerer is most often a sorceress.

They were often isolated widows living in poverty on the brink of society dependent on other people's charity. These females often had knowledge of healing, which assumed them to be capable of witchcraft.

Most scholars state that the belief in Native sorcerers originates from a superstition imported from France that associated strangers with sorcery.

On the Mi'kmaq side, however, there was no evil will, and the Mi'kmaq also wanted the Acadians to live nearby to gain access to their priests.

According to Leger, Acadians could attain power from people who came from France. Others could receive their powers through heredity or a friend.

According to Speck, there were among the Penobscot, both male and female shamans, and the female was "the more virulent manifestation.

According to Denise Lamontagne, feminine power in the Western European imagination is symbolized by the double image of the sorcerer and healer.

This image was then applied by the Acadians to the Mi'kmaq:

"La taoueille constitue le côté négatif du pouvoir féminin, assimilé à la langue française, à l’autre représente par la personne autochtone dans l'imaginaire appartenant à la culture orale. "

Most witnesses do not call their healers taoueilles, and they claim that their cures were not formerly magical.

According to Ronald Labelle, Acadians speak of "gifts" and "secrets," and they look at healers as practitioners rather than as supernatural agents even when cures appear to be miraculous.

Copyright © 2019 Louisiana Agriculture Preservation Society - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder