Mesopotamia

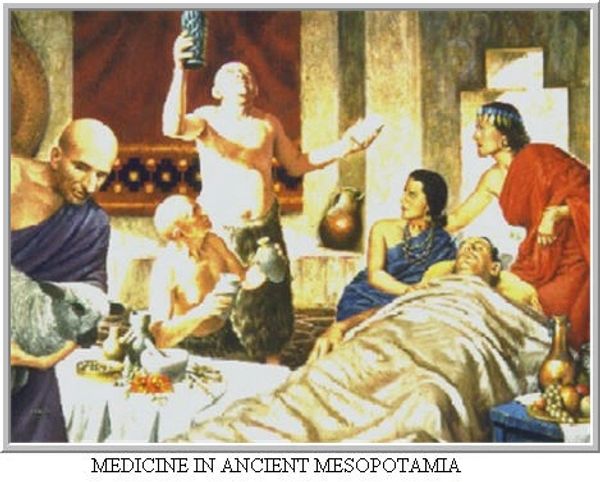

Introduction

Medicine has a lengthy history in the Middle and Near East. The earliest known medical records come back to ancient Mesopotamia and start around 3,000 BC in Sumer.

Medicine and religion, like all ancient cultures, went hand in hand. If a person was diagnosed with a disease or illness, it was regarded as the displeasure of the gods with that person, or as a manifestation of evil spirits dwelling within that person.

Every spirit or god was held accountable for just one disease.

Medical Practitioners

Alongside the Ashipu, a particular class of people was regarded as Herbal Practitioners (The Asu).

An Asu was also seen as a doctor specializing in herbal remedies and had a strong knowledge of the characteristics of various herbs and minerals.

They dealt with the empirical applications of medication.

For instance, the Asu usually depended on washing, bandaging, and producing the first plaster from a combination of medicinal and herbal products, as well as allowing certain herbs to be swallowed or applied to diseases when treating injuries.

As part of their profession as housekeepers, female healers or doctors, women produced all medications in Mesopotamia.

The woman would take the position as an Asu at times. An Asu, who was a doctor and specialized in herbal remedies, composed a thorough knowledge of the characteristics of various herbs and minerals.

Plants or crops they grew in those days were the fundamental components used to produce creams and ointments through plant components, livestock, and their products.

Such products were ingested or inserted into the body or applied to the surface of the body.

Over time, each herb's characteristics were studied, and individuals found how to treat each disease.

The most prominent surviving medical treatise of this kind from ancient Mesopotamia is known as "Medical Diagnosis and Prognosis Treatise."

The text of this treatise comprises of 40 tablets gathered and studied by French scholar R. Labat.

Although the earliest surviving copy of this treatise dates back to about 1,600 BC, the data contained in the document is an amalgamation of Mesopotamian medical knowledge of several centuries.

It has been shown that the crops used in therapy were usually used to treat the disease's symptoms and were not the kinds of stuff that were traditionally provided for magical reasons.

At that time, the same crops were used as today.

The most important crops in Mesopotamia were wheat and barley.

Farmers also grew

- dates,

- grapes,

- figs,

- melons,

- apples.

Favorite vegetables included:

- eggplants,

- onions,

- radishes,

- beans,

- lettuce,

- sesame seeds.

Mesopotamians also raised sheep, goats, and cows as a source for food.

Hoping for a plentiful crop, farmers worshipped Baal. Baal was a major Mesopotamian god of the sun and plentiful crops. They also

worshipped Ashnan, the Sumerian goddess of grain.

The farmers of Mesopotamia were inventive. They made bronze hand tools, like hammers, sickles, axes, and diggers. Mesopotamians were probably the first to use the wheel. By 3000 BCE, they had invented the plow and the plow seeder.

Mesopotamians even published manuals explaining how, and when plants should be planted. They also had a moon-based calendar to help the peasants.

Throughout the lengthy history of Mesopotamia, many civilizations have risen and fall. Among them were the Akkadians, Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. However, since they all cultivated the same plants and domestic animals, their diets were undoubtedly comparable.

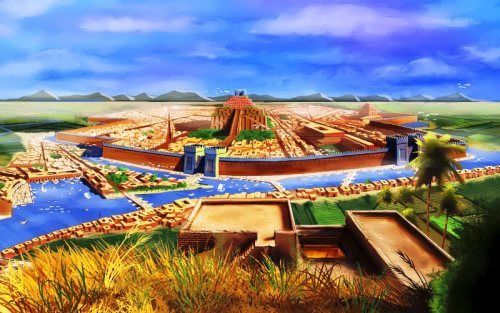

The name for "Mesopotamia" derives from a Greek word meaning "land between rivers," such rivers being the Tigris and the Euphrates, or what is now Iraq, Jordan and Syria.

Archeology and the old cuneiform text show the significance of barley. The citizens produced bread and beer from barley, which were the ingredients of their diet. Grains such as barley and wheat, and also legumes including:

- lentils and chickpeas,

- beans,

- tomatoes,

- garlic,

- leeks,

- melons,

- eggplants,

- turnips,

- lettuce,

- cucumbers,

fruits:

- grapes,

- plums,

- figs,

- pears,

- dates,

- pomegranaes,

- apricots,

- pistachios

and a range of plants and spices were all cultivated and consumed by Mesopotamians.

Mesopotamians drank beer for the most part and lots of it. Wine was also a part of their favorite drinks, but it was more expensive.

Mesopotamians drank loads of beer for the most part.

Herbal medicine and other pharmaceuticals in ancient Mesopotamia were omnipresent instruments used by Asu doctors.

Some treatments were likely based on empirically discovered characteristics of the ingredients used. In contrast, others were less based on efficacy and more based on the attribution of superstitious or symbolic qualities.

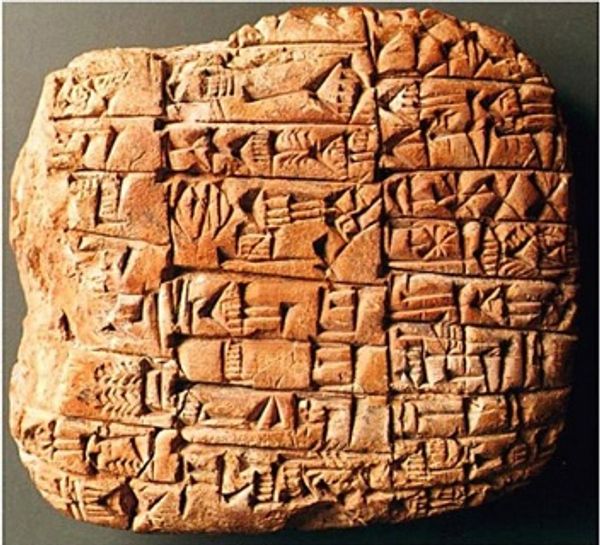

A cuneiform Sumerian tablet from c. 3000 BCE lists fifteen pharmaceutical prescriptions, although the meaning given by the names of the related illnesses or the quantities of the components is lacking.

The elements of the treatments are faunal, botanic, and mineral:

- sodium chloride (salt),

- potassium nitrate (saltpeter),

- milk,

- snakeskin,

- turtle shell,

- cassia,

- myrtle,

- asafetida,

- thyme - The Ancient Sumerians used Thyme as an antiseptic as far back as 3000BC.

- willow,

- pear,

- fig,

- fir,

- date.

All parts of plant anatomy were utilized: branches, roots, seeds, bark, sap, and branches.

These essential components were administered in vehicles of honey, water, beer, wine, and bitumen, as poultices and internal medicine.

While this is the only text among few that have survived, it offers insight to a more versatile pharmaceutical tradition that might be expected; the several ingredients named on the tablet were recombined into laxatives, detergents, antiseptics, salves, filtrates, and astringents.

Opiates were another class of botanical medicine that was utilized by the ancient Mesopotamians: narcotics were derived from Cannabis sativa (hemp), Mandragora spp. (mandrake), Lolium temulentum (darnel), and Papaver somniferum (opium).

There is evidence that opium poppies were definitely present in Sumeria by 3000 BCE, but they were probably reserved for use by Ashipu and priests in healing temples, and they were used in conjunction with hemlock as euthanasia.

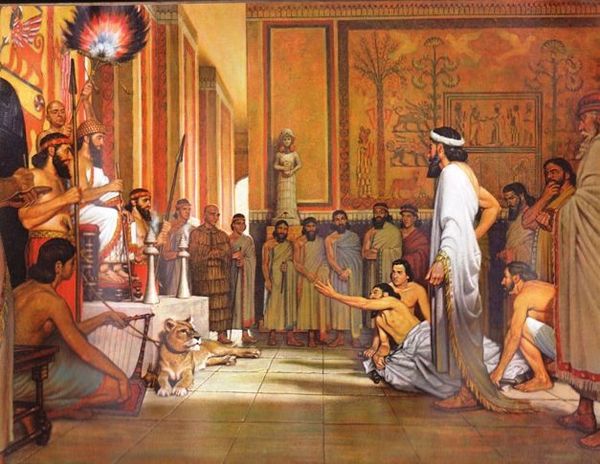

It was essential to determine the precise demon that was considered responsible for the disease and the reason why the demon behaved as such, when proposing a diagnosis. This immediately affected the prognosis.

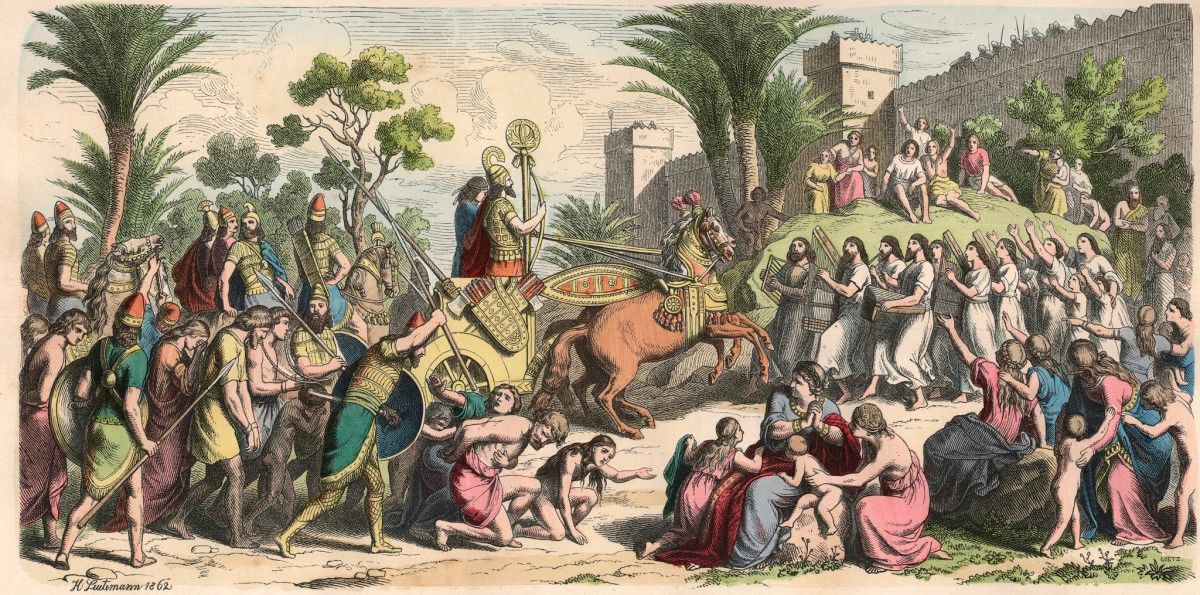

Treatment was primarily aimed at removing the demon or evil spirit responsible for the affliction, or at appeasing the angry gods. Having identified the cause through divination, an appropriate religious procedure would then be instituted, uttering incantations and spells, wearing amulets and charms.

A demon, if present, would be exorcised by the Ashipu.

When operating, witchcraft would be demolished by fire and water, and heavily dealt with by reputed sorcerers.

Additional treatment was often quite empirical in nature and included a wide range of medicines, including fumigations, suppositories and enemas.

There is no proof of nutritional therapy, but massage, manipulation, and therapeutic baths have been used. Although there is no Mesopotamian treatise on surgical methods, different surgical procedures have indeed been conducted (including a dental job) and trephination.

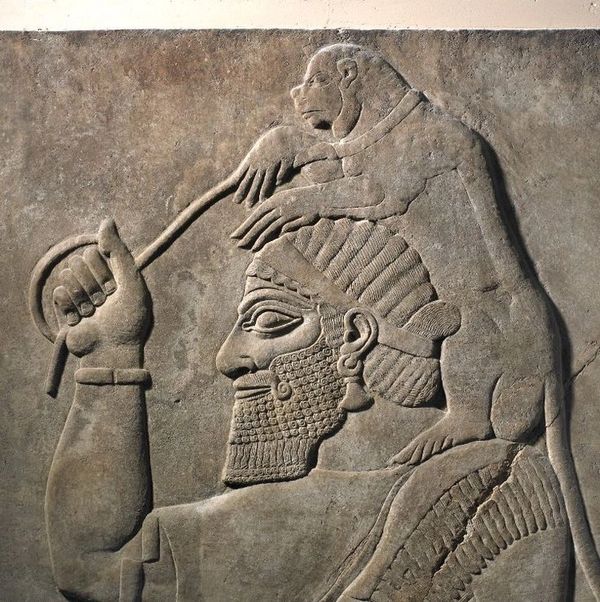

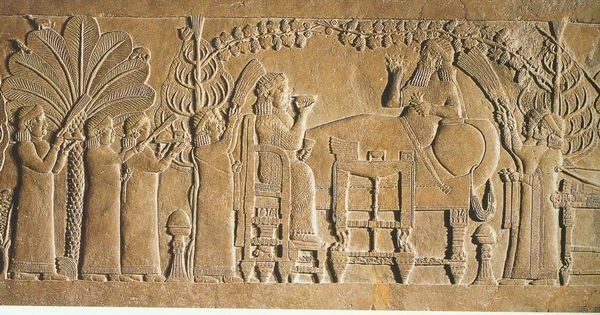

The Knowledge which we possess of the Assyrian Herbalism is derived from the baked clay tablets and fragments which have been found among the ruins of the vast Library of the temples at Nineveh and the loyal Library of Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, b.c. 668 - 626, at Nineveh.

This king was a great patron of learning, and he spared no pains in filling his Library with a series of well-made, well-baked, and carefully written clay tablets dealing with grammar, history, religious and profane literature, magic, omens, incantations, divination, astrology, etc.

Photo Gallery

Copyright © 2019 Louisiana Agriculture Preservation Society - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder